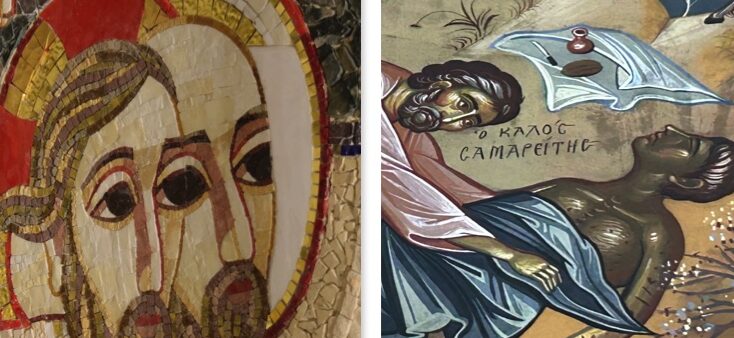

The top-left picture was drawn by Fr. Mario Rupnik SJ. The top-right is an icon I snapped at the Greek Catholic Church in Athens earlier this year. National Catholic Register wrote about the Jesuit who drew the above left picture: “Father Rupnik, a priest and artist, has been accused of spiritual, psychological, and sexual abuse of religious sisters. He was removed from the Jesuits last June.” Even the Knights of Columbus wanted his removed from the National Basilica in DC as Detroit Catholic reported. It’s unfortunate that “art” which mocks Our Lord and Our Lady and the saints is asked to be removed only once “the artist” is found to be a sexual criminal.

Rupnik’s “art.”

Recently, GloriaTV quoted Mr. Martin Mosebach, a German traditionalist and author, in saying that Catholic art globally “had embraced a theology that dissolved the Gospel into the abstract-philosophical or secular-political” due to a “Church that was moving ever closer to the areligious zeitgeist.” I couldn’t agree more. Regarding the art of Rupnik (above) Mosebach asked: “How can one expect anything else from artists but weakly sketched corpses or eyeless dolls mounted in front of crosses?” I think that is a perfect description of the center of these odd Catholic icons: Eyeless-dolls.

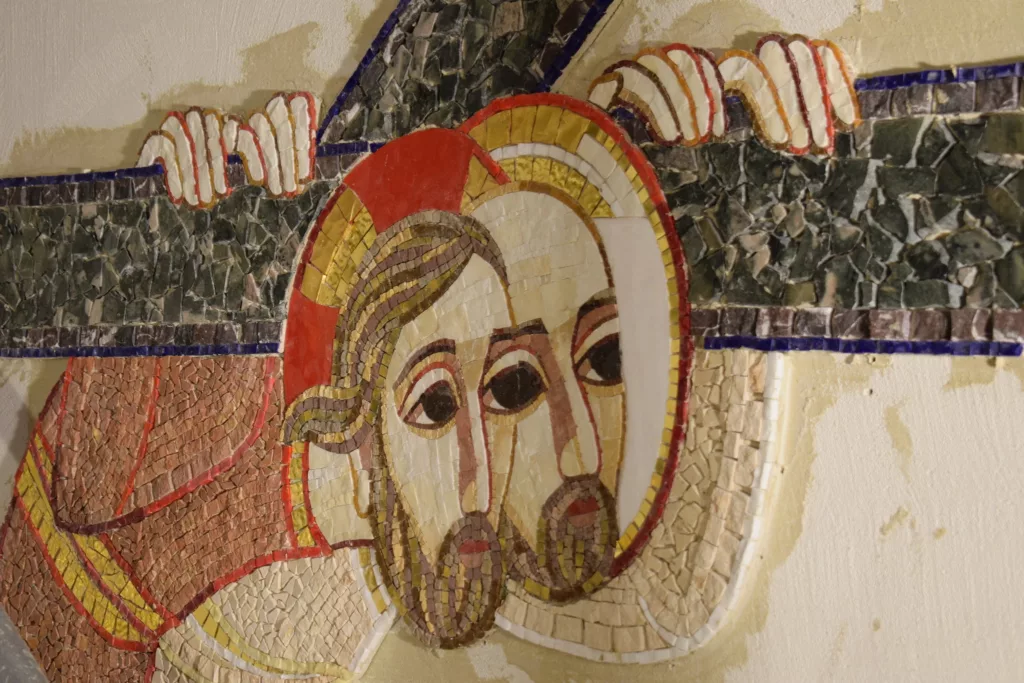

“Oregon Catholic Press” cover

Growing up at a liberal Catholic parish, every weekend I had to pick up some Oregon Catholic Press book like the above to sing some campy tune. Only later in my 40s did I realize what the art on the front of OCP conveys: Saints and Kings are portrayed as stupid, non-divine and even non-human always end up easily-manipulatable. Whoever that is (Our Lord? A saint? One of the Three Wise Men?) is meant to look like a schizophrenic homeless man. Why? Because if the Author of the Life is an easily-manipulatable man, then so is His doctrine.

Mr. Burns in Season 8 of the Simpsons. “I bring you peace!”

In 1997, the 10th episode of season 8 of the Simpsons was called “The Springfield Files” which had a guest appearance of X-Files Mulder and Skully investigating a green-paranormal person in the forest outside the Springfield Nuclear plant. The normally-grumpy Mr. Burnes was found glowing green and amazingly kind, as he was found saying “I bring you peace. I bring you love!” (You can see the five-second clip here.) It turns out Mr. Burns was not an alien at all. Rather, as the SimpsonsWiki explains, “The green glow’s a result of Burns spending a lifetime working in a nuclear power plant.” Secondarily, his glow was because Mr Burns underwent “a series of medical treatments designed to help him cheat death for another week.”

Every time I see a Rupnik or Oregon Catholic Press drawing of Our Lord or a saint, I think of that zombied-out Mr. Burns saying in a falsetto voice, “I bring you peace. I bring you love!” What’s the theology behind this? If the person you are called to adore (Christ) and the people you are called to venerate (the saints) can be portrayed as intellectually-weak and gender-non-specific, then anything goes in theology. As Mosebach said, they want “weakly sketched corpses or eyeless dolls mounted in front of crosses.” Art always reveals theology. That’s why the lukewarm were way behind the 8-ball in asking his art to be removed only after he was found to be a sexual criminal.

Let’s get to some good art…

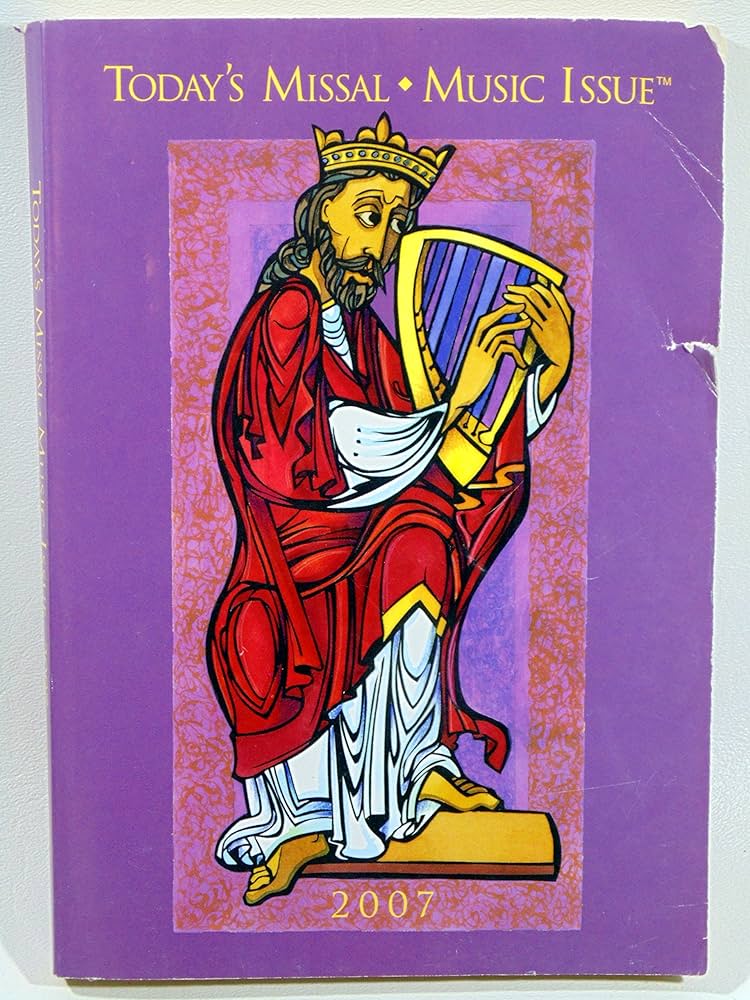

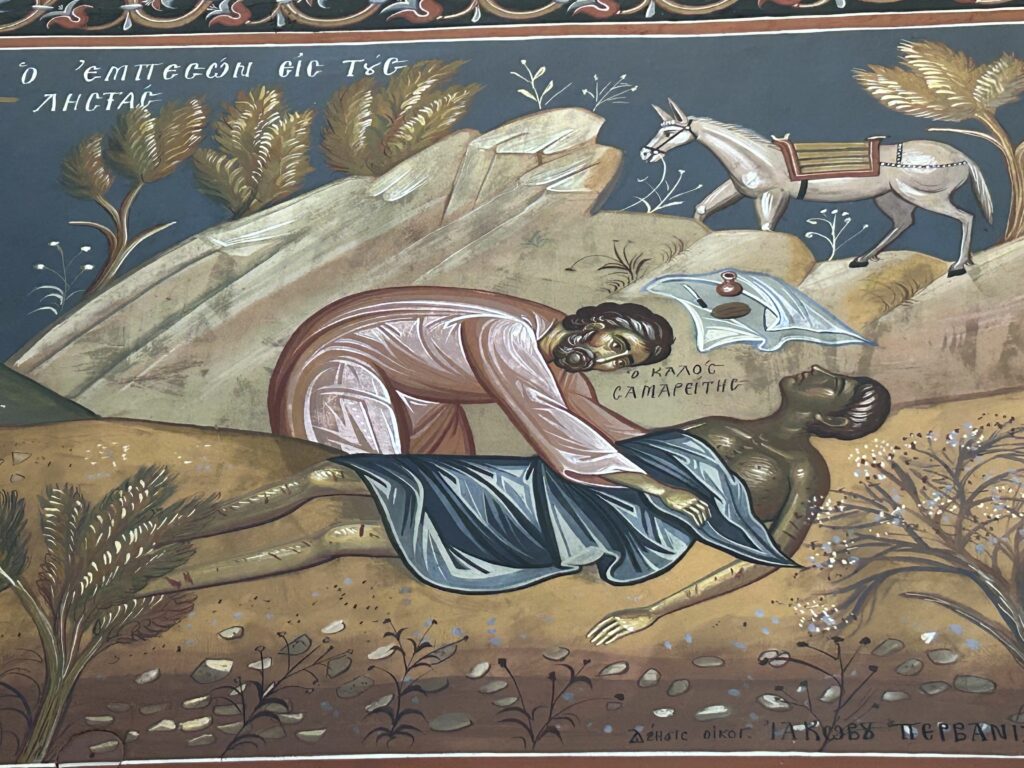

Good Samaritan icon in Greek Catholic Cathedral of Athens.

The above picture is an icon I snapped in the Greek Catholic Cathedral of Athens. The name of the Cathedral is “Holy Trinity.” (I saw plenty of beautiful Greek Orthodox art in Athens, too, but notice the above and the below pictures are in the Greek Catholic Cathedral in Athens.) Notice that in the above icon, the eyes are not melded together. In Eastern religions (I don’t mean Eastern Catholic or Orthodox Churches) but in actual Eastern religions (like Hinduism and Buddhism) the notion of the individual in melded into the other in an amorphous reality which ultimately contains no responsibility for the moral life. (This is very much like Rupnik’s art or that of OCP.)

But in the Good Samaritan icon above, we see that the Good Samaritan is a different person from the person who was accosted by robbers. They do not share one set of eyes. There is human-individuality and even a firm responsibility of the moral life seen in the icon. Most importantly, it is beautiful and transcendent. It’s not the most beautiful icon I have ever seen, but it captures the strength and compassion of the Good Samaritan without being saccharine sweet.

SS Cyril and Methodius in Greek Catholic Cathedral of Athens.

The above is another icon I snapped in the Greek Catholic Cathedral of Athens. It is an icon of Saint Methodius (left) and St. Cyril. These were the two Greek blood-brothers in Greece of the 9th century who were sent from Rome to the Slavic countries to spread the Gospel. These icons are windows into heaven. You see the brothers’ holiness shining and you are drawn into their union with God as well as their Apostolic teaching, simply by gazing upon this icon. Their faces are serious but not angry. Their eyes are kind but sober, and even serious. Saints Cyril and Methodius show that their Savior’s Gospel is not something manipulatable but rather unchangeable. This is what Catholic art should do: Direct the gaze of the viewer to the transcendent to see the unchangeable and beautiful truths of Divine Revelation. Not focus on man, especially not perverse man. Our eyes are made for God if we are to experience the beatific vision, and good art truly helps us prepare for that.