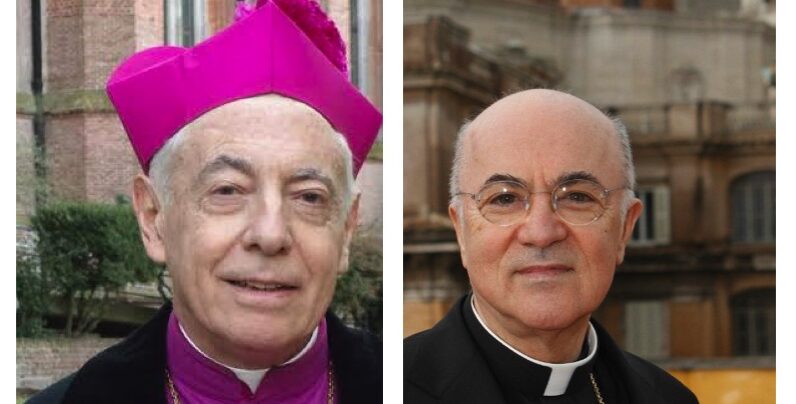

Archbishop Emeritus Héctor Aguer of La Plata, Argentina recently wrote about cancelled clergy. His letter is especially important in light of recent news on Bp. Strickland. Rorate Caeli had the full translation, so I reproduce it here:

1. Priests cancelled. I am not dealing now with what is happening at the international level, but with a phenomenon that is becoming more and more frequent in Argentina, in various dioceses. “Cancelled” is equivalent to a displacement to non-existence when counting the official number of priests who serve as clergy in a particular (diocesan) church. They are deprived of the means to exercise the ministry and are disavowed before the faithful.

They are accused of being “traditionalists,” even though they do not move according to an ideology. Ideological, rather, is the principle of cancellation, which arises from an elementary and shameless progressivism. Unfortunately, the authors of this injustice are bishops. I have to think that they do not know what they are doing, the unjust harm they are causing — which does not justify them as innocent. The cancellers, they who fill their mouths talking about love, are dramatically responsible for such an attack against charity. The number of cancelled priests has grown lately, and this reality exhibits a mysterious side, because it is the mystery of the Church that is affected, the substance of charity that suffers an impairment.

The remedy begins to be found when the fact is acknowledged, and it slips by without the press taking note of it, not even to discredit the Church. With this brief mention of the problem I want to encourage, once again, a possible and necessary solution.

On the other hand, the cancelled priests — it is inevitable that they recognize their situation — have the providential opportunity to unite themselves to the Passion of the Lord and not to harbor feelings of hatred, but to strengthen themselves in hope and to attend discreetly to the faithful who approach them. “Every cloud has a silver lining,” goes the popular saying. Another saying: “There is no evil that lasts a hundred years.” By denouncing the phenomenon, I am contributing to making it publicly known and to remedying a situation caused by this deliquescent progressivism that is spreading to the detriment of the Church and to the detriment of the priestly order.

2. What successful parishes look like. I would like to highlight a fact registered by the ecclesial x-ray, a fact that illuminates the reality of the Church. The fact is a contrast, or rather the result of a contrast: it is the “success” of a parish community (analogously, one could eventually say of a diocese) in which Catholic Tradition is lived. (I write “success” in quotation marks because the word has a tinge of worldliness to it.)

Simply put, the reality of Christian life, so often today fallen into banality, is truly lived there.

• The parish priest and other priests who serve there preach the truth unabashedly; they do not ideologize it, but the truth is expressed openly and normally, as all preaching should be.

• Confession is widely offered to the faithful, and in Confession the criteria of Catholic morality are applied, without compromise with the relativistic lines that are ubiquitously widespread.

• The liturgy stands out from the universal mediocrity that harms the liturgical mystery; it is characterized by exactitude, solemnity, and beauty.

• The chants come from the traditional collection that has been formed over the years, although recently well-composed pieces are also included. It is true music, not simplistic “guitar music.”

• The youth groups, with many members, spread authentic spiritual life and missionary spirit to the new members who join.

• The practices of piety are characterized by seriousness, without any kind of mannerisms that are not conducive to personal and community growth in the faith.

In short, such parishes of today are parishes as they should always be: normal (although it may seem strange to use the term!), that is to say, as Catholic as they are very much up to date. Tradition is a lived reality, not a declamation; it is what has always been, insofar as what has always been remains current and is no museum piece. There is no question here of “traditionalism,” if -ism means an exaggeration by abuse and manipulation.

3. Silenti opere (with silent work). The expression comes from the post-communion prayer of Mass 8 of the Marian Missal. One could think that this silent work was the occupation of the Blessed Virgin and St. Joseph, who always worked in the silence of God. Because God is characterized by profound silence.

To refer the expression to ecclesial life, and to the current x-ray of the Church, it could be translated as “It is better that they do not notice.” This caution frees us from the exhibition, or exhibitionism, in which pride is hidden, the thought that “we are better.” It also rescues the body in advance from some possible form of cancellation. This thought is proper to realism and to the knowledge of the life of the Church at the universal and national level. The figures of Mary and Joseph are well suited; they went unnoticed by the world and the Judaism of their time. Exhibitionism is always dangerous; it can fall into the “run, run, run” of journalism. We are as we are for God, and only for Him.

Previously I have said that the description of a “successful” parish can be applied analogously to a diocese. In this case the silenti opere and its translation “it is better that they do not realize it” have assumed that the bishop belongs to the Episcopal Conference. This organization oppresses each bishop and submits him to projects and programs that are supposedly common to all. If a diocese with a good clergy, where the Catholic truth is preached, where the liturgy is well cared for and the attention of the faithful, with its organisms of lay apostolate, is adequate — if such a diocese is “exhibited,” it runs the risk of some form of cancellation, which begins when the other bishops look at it and perceive the aroma of Tradition. The Episcopal Conferences are usually the organisms of progressive unification, and they do not easily tolerate a bishop making use of his freedom as a successor of the apostles and depositary of an original authority.

4. The Rosary of Men. Last October 7, the fourth annual Rosary prayed by men was held in Buenos Aires in Plaza de Mayo, in front of the Cathedral Church. In every massive act it is difficult to know the number of participants; there is a spontaneous tendency to increase it. This time there were about 300 (I prefer to “fall short”). Simultaneously, a similar prayer was held in several countries. The date had a profoundly symbolic meaning: it was the 452nd anniversary of the Battle of Lepanto, the triumph of the Christian army over the Ottoman army, which threatened the faith and freedom of Europe. The arms that fought under the Cross were under the command of Don John of Austria, brother of the Emperor Charles V. Pope St. Pius V had entrusted the circumstance to the Blessed Virgin and exhorted to invoke her by praying the Rosary; she would be Our Lady of Victory, patroness of the Crusade — because it was a Crusade, another episode of Christian resistance to the overwhelming advance of the Crescent.

In Plaza de Mayo the sincere and ardent devotion of the participants was noticeable: I was a witness. Although it is curious to interpret the episode in cultural and sociological terms, it must be said that it was a singular realization of the phenomenon that is recognized by applying the “gender perspective,” this time vindicating the masculine identity. Contemporary culture, shaped by extreme feminism, repudiates virility and discards the paternal figure; it does not recognize in it the projection of the paternity of God, according to the logic of the Incarnation. Moreover, the religious attitude is often slandered by being presented as a womanly occupation. The truth is that the man prayerfully expresses his virile nature as a gift and vocation of the original Creation, as God has made things; He looked at his work and it had turned out “very good.” This is what we read in the Book of Genesis.

On October 7, we prayed especially for the people of Argentina and for the conversion of their leaders. At the end of the Rosary, the Square was surrounded by people passing in front of the Casa Rosada, the seat of the national government. There is no need to emphasize the symbolism of this gesture; we entrust to the mercy of God the painful situation that Argentina is going through, with a 41% poverty rate and a level of destitution never before experienced.

5. Liturgical quarrels. Differences on liturgical issues were broached during the sessions of the Second Vatican Council, but they acquired the dimension of confrontation only in the postconciliar period. The first document approved by the great conciliar assembly was the Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium on the Sacred Liturgy. This text expressed a reasonable degree of renewal, but was later labeled “conservative”; such a judgment is no doubt exaggerated, but it suggests noting that the Conciliar Constitution contains a stern warning, which I quote ad sensum: “Let no one, even a priest, change, add or subtract anything on his own authority in the Liturgy.”

The real problem, and the consequent quarrels, occurred in 1969 with the promulgation by Paul VI of the “new Mass”, that is, the reform of the rite of the Holy Sacrifice, the work of the Consilium ad exequendam Constitutionem de Sacra Liturgia, presided over by Bishop Annibale Bugnini. This prelate, reputed to be a Freemason, was responsible for the substitution of a new Mass of Paul VI for the preceding Missal published in 1962 by John XXIII. The qualifier of “new” is fully justified: it is a creation of a new rite that differs in almost everything from the one consecrated by a tradition of many centuries, which since St. Pius V, in the 16th century, had remained largely unchanged. Criticism of the new rite was aimed at the essentials: the ambiguity of a missal in which the notion of sacrifice “evaporated”.

The main protagonist of the complaint against this creation was Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, an exemplary ecclesiastical figure and a consecrated missionary. The complaint was triggered by the compulsory introduction of the new rite and the persecution of those who disagreed with it. Lefebvre created the Society of St. Pius X to train priests; on this the Roman sanction fell, which led to an involuntary break. The pertinacity of Paul VI in imposing, as absolute, the obligation to adopt the new Missal of 1969 was astonishing. Little by little it became clear that another path should have been taken.

Lefebvre’s position grew in popularity for more than twenty years; an unusual division was created that damaged the union of discipline that, in the Church, is an expression of charity. It was John Paul II who began to put into practice a behavior of understanding and consequently tolerance in many cases. His successor, Benedict XVI, remedied the unbearable situation by widely allowing the use of the Missal published by John XXIII in 1962. This position was consecrated by the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum, on September 12, 2007, received with relief and joy by the Body of the faithful (except, of course, for the progressive sectors).

Unfortunately, this peaceful situation was altered by the current Supreme Pontiff, who in the motu proprio Traditiones Custodes, published on July 16, 2021, made it extremely difficult to use the 1962 Missal. It was now (supposedly) left to the discretion of diocesan bishops to grant permission to celebrate according to the immemorial rite that Benedict XVI reaffirmed, stating that the ancient Mass had never been abrogated. The great Pope Ratzinger restored peace to the Church, disturbed by liturgical quarrels. This last observation allows us to measure the damage inflicted by the motu proprio Traditiones Custodes; the bishops are not always custodians of Tradition, but many ignore it or fight against it. [And then there is the fact that Rome tries to control their “discretion” and their “freedom”… – PK]

The ecclesial x-ray reveals, without a doubt, numerous problems that could be focused on and which I will deal with — as the Lord benevolently permits — in other installments.

+ Héctor Aguer

Archbishop Emeritus of La Plata

Buenos Aires

Tuesday, October 31, 2023

First Vespers of the Solemnity of All Saints