And behold, a man came up to [Christ], saying, “Teacher, what good deed must I do to have eternal life?” And He said to him, “Why do you ask me about what is good? There is only One who is good. If you would enter life, keep the commandments.” He said to him, “Which ones?” And Jesus said, “You shall not murder, You shall not commit adultery, You shall not steal, You shall not bear false witness, Honor your father and mother, and, You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” The young man said to Him, “All these I have kept. What do I still lack?” Jesus said to him, “If you would be perfect, go, sell what you possess and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me.” When the young man heard this he went away sorrowful, for he had great possessions.—Mt 19:16-22

In Veritatis Splendor, Pope John Paul II uses the above account from Matthew 19 to attack the modern moral theology errors of “consequentialism” and “proportionalism.” The Pope accurately explains that consequentialism “claims to draw the criteria of the rightness of a given way of acting solely from a calculation of foreseeable consequences deriving from a given choice.” He continues that proportionalism “weighs the various values and goods being sought, focuses rather on the proportion acknowledged between the good and bad effects of that choice, with a view to the ‘greater good’ or ‘lesser evil’ actually possible in a particular situation.”—Veritatis Splendor #75. Both of these errors, consequentialism and proportionalism, are a far cry from how Christ answers so clearly: “Keep the commandments” to his questioner saying,”What good deed must I do to have eternal life?”

To understand proportionalism, imagine this account that has probably happened in most every diocese of the USA in the past 30 years: A bishop begins weighing all the hate-mail that repeatedly lands on his desk against a young, conservative priest. That bishop begins to judge that the peace of a diocese weighs greater than a particular priest’s priesthood. To avoid further troublesome effects in his chancery, the bishop decides to end the conservative priest’s active ministry by either lying about him or sending him to the psyche ward at St. Luke’s. The bishop does not want to end that young priest’s priesthood. He has just proportionately weighed that a few small lies about one soul is probably worth a thousands other souls not being disturbed enough to write letters to the chancery.

Now, if you’re convinced that the above imaginary bishop made an unfortunate but prudent decision, then you just sided with the proportionalism that led the high priest Caiaphas’ to kill Jesus Christ: “It is better for you that one man should die for the people, than for the whole nation to perish.”—Jn 11:49-50. Astonishingly, Caiaphas almost seems to admit that killing Jesus is a bad idea! Indeed, Caiaphas figures that killing Christ will have proportionately less detrimental consequences than a schism within Israel which might eventually attract the attention of the Roman Empire. Orthodox but cowardly prelates today should remember that the one thing that Caiaphas feared—the Roman Empire destroying the temple 40 years later—was exactly what he effected by setting into motion the execution of Jesus Christ by using proportionalism! St. John notes a few verses later that Caiaphas’ ability to become a self-fulfilling agent in Christ’s death (albeit accidentally and sacrilegiously) was an effect of being high priest that year: “He did not say this of his own accord, but being high priest that year, he prophesied that Jesus would die for the nation.”—v. 51.

To understand consequentialism, imagine this story that has also proved to be unfortunately quite common in most dioceses of the USA beginning in the 1970s: A certain bishop receives numerous, credible reports that a certain priest molested children. The bishop then decides to lie to the public about that priest, but this time the bishop makes the priest out to be better than he is. He says he is still “fit for public ministry.” The bishop did want not want to lie to his diocese about a predatory priest. It’s just that he believed that doing the right thing in the present, namely, sending the child-molesting priest to prison, would lead to bad consequences in the future like many Catholics leaving his diocese. (Like Caiaphas, this is exactly what would happen 40 years later due to his actions!) This error of using consequentialism to make decisions in a diocese shows that evil never pays. Remember that Pope John Paul II described the moral theology heresy of consequentialism as “claim[ing] to draw the criteria of the rightness of a given way of acting solely from a calculation of foreseeable consequences deriving from a given choice.”—Veritatis Splendor#75. (Unfortunately, Pope John Paul II seems to have turned a blind-eye to the complaints that started to pour into the Vatican in 1998 regarding Fr. Marcial Maciel being a child-molestor. Was the Pope incredulous as to the accusations? Or was the Pope using consequentialism in his decisions to protect that wicked demiurge and juggernaut founder of the Legionaries of Christ?)

For a decision to be moral, it must have a good intention, a good object (act) and good circumstances. Catholic moral theology has always infallibly taught that if even one of these three is missing, it is bad decision. Thus, if you refrain from speaking the truth while maintaining a good intention (eg keeping the diocese together or preventing the schism in the Church) then you have committed a mortal sin. In short, the end does not justify the means. This is very basic stuff. But proportionalism and consequentialism are just Satan’s advanced loopholes around this. Perhaps the problem is pride—that we preists and priests and bishops and Cardinals and Popes think that our proportions and consequences of the future of the Church somehow outweigh us doing the right thing in the present. It might be just this basic error that we don’t think that moral theology applies to us, especially when we have a whole Church’s image to repair amidst distressing scandal.

Bishop Gracida of Texas is a great hero of mine for publicly questioning the valid resignation of Pope Benedict XVI. I know for a fact that at least one other Cardinal in the world is questioning this, too. But even if you do not buy our “resignationalist” approach to the current crisis, then at least ask this: Where are all the bishops denouncing the weekly heresy that we are now hearing from the top down? I don’t mean that liturgical digits are being denied by people in the Vatican. I mean basic tenets of the Creed are being overturned on a weekly basis. Most good bishops of the world now know that parts of the Creed are being publicly denied in material heresy. But if you were to quietly ask any decent bishop or Cardinal why he does not oppose the current errors coming at him from the hierarchy above him, and even in the Vatican, he would probably sigh and say, “And just get in trouble and lose my diocese? Then you’d just have some liberal bishop replace me!” This seems like a conservative and strategic answer. Unfortunately, his answer is mortally sinful since it is based on the moral theology heresy of consequentialism. Here is why: The end does not justify the means, whether those means be sins of commission or omission. Have you ever thought of the fact that sins of omission do not justify a good end?

That means that if I refrain from correcting heresy in the those above me for the sake of keeping my faculties just to hear another 10,000 confessions, I commit a mortal sin based on the moral theology heresy of proportionalism. If a certain bishop were to tell us that doing the couragous thing would be all “too human” and that we should wait around for divine intervention, this would be approaching the spiritual heresy of quietism. If a certain Cardinal were to refrain from correcting the heresies of those above him so as to save the Church from schism (read: Caiaphas) or if that Cardinal were to stay silent so as to save his own hide to one day to become Pope, this too would be the moral theology error of consequentialism. Consequentialism and Proportionism are the two moral heresies freezing every prelate of the world from doing the right thing in the worst crisis in Church history. The end does not justify the means, even if those means are sins of omission with the good intention of your ministry’s self-preservation, or even preservation of the Church against schism.

Correcting another’s heresy (even those above us) is not only a heroic act, but a necessary act according to St. Paul and St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas: “It must be observed, however, that if the faith were endangered, a subject ought to rebuke his prelate even publicly. Hence Paul, who was Peter’s subject, rebuked him in public, on account of the imminent danger of scandal concerning faith, and, as the gloss of Augustine says on Galatians 2:11, ‘Peter gave an example to superiors, that if at any time they should happen to stray from the straight path, they should not disdain to be reproved by their subjects.”—St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologicae II.II.33 art 4 reply to objection 2.

Many prelates would respond to the above with a sign of resignation: “Ahh, but no one would listen to me, anyway! I’m just a bishop of a small diocese in the Philippines.” Well, look at what God tells the prophet Jeremiah: ““When you tell them all this, they will not listen to you; when you call to them, they will not answer. Therefore say to them, ‘This is the nation that has not obeyed the Lord its God or responded to correction.’”—Jeremiah 7:27. Look at that first sentence again. Have you ever heard of a mission that God has sent a man on where he has already told him that he will fail? It’s astonishing that God tells Jeremiah ahead of time that the nation of Israel “will not listen to you.” Jeremiah obeys anyway. Why? Because it is GOD! It is GOD telling him too. Does that not mean anything to anyone anymore in the Catholic Church hierarchy? Jeremiah does not have time for the heresy of consequentialism by arguing that “no one will listen to me.” Yeah, God already told Jeremiah that. We obey God, anyway.

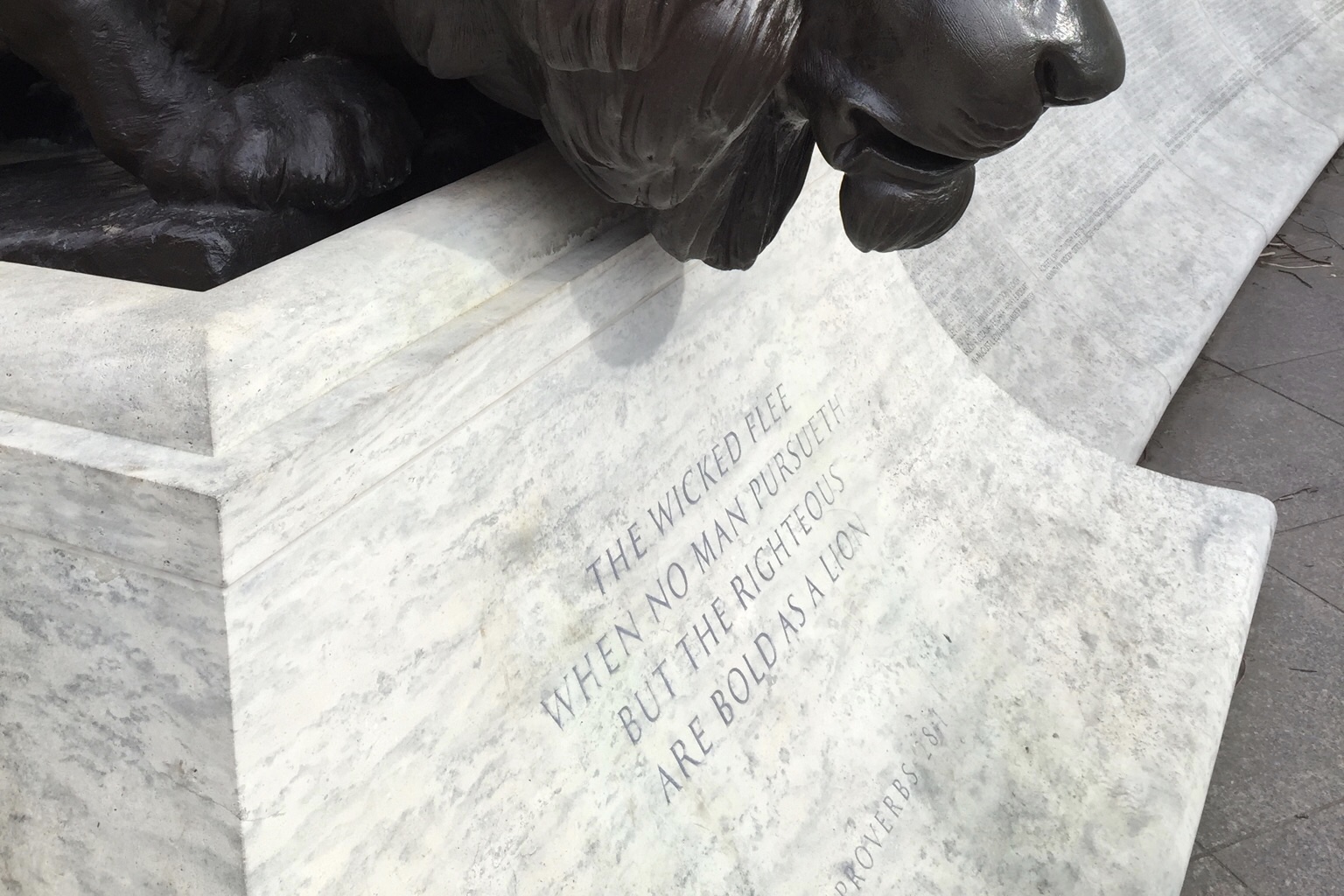

Look, this is not me just being a weekend warrior with a keyboard or a mere priest who is virtue-signaling against a hierarchy because he has to be a hermit. I’m using big words like “consequentialism”and “proportionism”because that is what moral theologians have called this error. But you don’t need to be a moral theologian to do the right thing as a father, spiritual or biological. Imagine this: Imagine a biological father is walking in the mountains of Colorado with his seven children. Imagine a mountain lion attacked one of his children. Would that father go and fight off that mountain lion? Yes! What if it cost that man his life? He would still do it. Can you imagine what kind of bad father would do an internal proportionalistic debate when a lion attacks his daughter? It might go like this: “Well, if I go and fight that lion off my oldest daughter, then it might kill me, and then my other six children would have no father. It is probably better that I leave the lion to eat my daughter because I would not want my other six children to be raised fatherless.” Such is the reasoning of why so many bishops will lie. They love their own digs more than the salvation of souls. But the opposite of proportionalism is what comes naturally to any virtuous father, biological or spiritual: Do the right thing. Always. Regardless of consequences, regardless of a weighed outcome.

And some bishops have done the right thing in history, regardless of consequences, even knowing of a coming failure that would cost them their seats in the diocese.

For example, in the 4th century, St. John Chrysostom was the Archbishop of Constantinople, the second most important city of Christendom behind only to Rome. Hundreds of thousands of people in modern-day Turkey looked to this great preacher to guide them to holiness. But one day, St. John Chrysostom knew he had to rebuke the Empress Eudoxia. St. John knew her temporal power. He knew very well that if he rebuked her, he might lose his seat as Patriarch over Constantinople. He knew that his people would be like sheep without a shepherd. He knew that hundreds of priests would go without his guidance in their ministries and perhaps thousands of the laity might fall away from the sacraments.

So, what did St. John Chrysostom do? He not only rebuked the Empress. He did it at Divine Liturgy. He called her a “Jezebel” publicly! Of course, she sent him into exile. Twice. Both times, Chrysostom had to leave his beloved Constantinople and her people. But he was simply reported to say at that time: “Violent storms encompass me on all sides, yet I am without fear because I stand upon a rock. Though the sea roar and the waves rise high, they cannot overwhelm the ship of Jesus Christ.” Chrysostom returned months or years later, one night. The people got wind of his return, and thousands went out on boats on the Bosborus, lighting up candles in the night to welcome their beloved spiritual father back! So, we must ask: What were the consequences of him not following the moral heresy of consequentialism? Of him not weighing souls of tomorrow against doing the right thing today? The answer to this is that St. John Chrysostom got canonized. St. John Chrysostom got declared a doctor of the Church. St. John Chrysostom was to then be read by millions of Christians, East and West, and people will be reading St. John Chrysostom until Christ returns in glory. Most importantly, St. John obeyed God and subsequently became a hero to all the biological fathers of Constantinople in that 4th century who desperately wanted to see a soldier of Christ do the right thing without compromise or fear.

Finally, pardon the borderline-blasphemy, but imagine if Jesus Christ had followed the moral theology errors of proportionalism and consequentialism. If Jesus Christ had followed these two moral theology of the end justifying the means, it would have sounded something like this: “I have a good thing going with these life-changing miracles and powerful teaching. If I keep telling the Pharisees that they are hypocrites, they might end my healings and terminate my raising people from the dead. If I oppose the Pharisees anymore, they will certainly end the most important thing: My preaching of My Father’s Kingdom! Thus, I better make peace with the Pharisees, because if they crucify me, then my awesome ministry ends!”

Of course, this type of thinking was exactly how St. Peter saw things when Jesus had to rebuke him and call him a “Satan.” Jesus knew that it was a temptation to put worldly success—even in ministry—above doing the right thing that would lead to the cross. Christ had to shock-therapy Peter into seeing at that moment that the world would not be saved without the cross, and that Christ could not climb the cross by weighing measly human consequences on the future when He was called in his Sacred Humanity by His Own Sacred Divinity to do just one thing: The right thing, today, without compromise, even if it meant raising the ire of the religious leaders of His day.

Yes, such an act amidst a corrupt hierarchy will usually lead to the end of one’s ministry…and the redemption of the world.

1