Myth 1: Catholic means universal, as in what all Catholics believe in the 21st century.

Truth: Catholic is that which is believed everywhere, always and by all.

Many people believe that the term “Catholic” means universal in Latin. This is true, but the Greek root of this word is even older:

As you can see, Catholic means “according to the whole.” By whole, that means everything in the Bible and oral tradition (2 Thess 2:15.) It means the fullness of the truth. The modern myth is that “Catholic” means universal—but only today. The problem with this definition is that it falls short of the original Patristic definitions of Catholic. The fifth century monk St. Vincent of Lérins taught: “Moreover, in the Catholic Church itself, all possible care must be taken, that we hold that faith which has been believedeverywhere, always, by all (quod ubique, quod semper, quod ab omnibus creditum est.)”—St. Vincent of Lérins, Commonitorium 4. Thus, Catholic doesn’t mean that quasi-deposit of the faith which is believed universally in an isolated époque of history, but rather the common teaching of the Popes and Fathers and saints of the 2nd century and the 8th century and the 13th century and the 17th century, and every century of the Magisterium.

Myth 2: Church History is like a pendulum that swings back and forth between conservative and liberal.

Truth: Church history is politically unstable, but dogmatically quite stable, except for two unique doctrinal crises in Church history. Even in these periods, the Magisterium remains untouched.

I graduated from a Jesuit high school and a Jesuit University and then I had another several years of Jesuit spiritual direction in seminary. I owe the Jesuits a lot, at least the true sons of Ignatius. But one of those false-sons of Ignatius tuaght us at some point in high-school that Church history is like a pendulum that swung back and forth between “conservative” and “liberal.”

For perhaps a decade, I promoted this odd teaching.

But as I started reading Church history, I never found a century when the pendulum went to “the left.” I found that St. Ignatius of Antioch (1st century) taught the same thing about salvation outside the Church as St. Alphonsus Liguori (18th century) as St. Theresa of Avila (16th century) as, yes, even every liberal’s favorite mascot, St. Francis of Assisi. Before that, I would happily remind people in my high-school days that “St. Francis of Assisi said that we should preach the Gospel always; use words if necessary.”

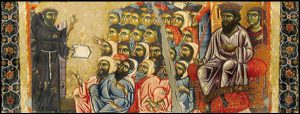

Well, then I found out that St. Francis of Assisi believed words to be so necessary to the preaching of the Gospel for the salvation of Muslims that he actually went to Muslim lands to preach to the Sultan the Gospel of Jesus Christ and His Church:

Thus, there was no pendulum swing to “the left” as we had been taught. It was always on the right, with every saint teaching that “No one comes to the Father except through me.”—John 14:6. In other words, if everyone’s favorite ecumenical mascot St. Francis of Assisi wrote “woe to those who die in mortal sin,” then there are no saints of the left-leaning pendulum. If St. Therese of Lisieux fasted as a child from not only food, but also water to save the criminal Pranzini as he approached the gallows, then who are all these Methodist-sounding saints before, say, 1950? When, before our odd modern times did the pendulum swing to the left? Was it in the 8th century? Or the 16th century? Who are these mysterious ecumenical saints of the 2nd century or the 13th century or the 18th century? Who are the saints of the pendulum leaning left and away from traditional Catholicism? I never found any. Write me if you do.

The only explanation is that we don’t have a pendulum swing. We have solid and normal and beautiful Catholicism for 20 centuries, all except the Arian crisis and the current modernist crisis.

Bishop Athanasius Schneider of Kazakhstan names the crises of the Church here including:

1) The Arian heresy, about which I podcasted here yesterday.

2) The Dark Century of the Roman Mafia

3) The Great Western Schism

4) Today’s Anthropocentric Crisis that Bp. Athanasius describes as “doctrinal, moral and tremendous liturgical anarchy.”

Notice that there have been four great crises in Church History, but see that exclusively number two and number three refer mostly to politics of the Church, not much doctrine. But the first crisis (the Arian crisis) and today’s crisis (the anthropocentric crisis) is doctrinal first. That means that essentially, these are about the only times in history when nearly all Catholics have almost globally and entirely diverted from Catholic Deposit of the Faith on matters “doctrinal, moral and liturgical” as His Excellency has pointed out. Indeed, we have a pretty unbroken tradition of what was taught always and at all times in an Apostolic manner, except for two unique crises when dogmatic relativism ruled even the hierarchy.

It is no wonder that our liturgy is so different from every single century, either.

The most recent shocker of this new mis-narrative in Catholic Church history is that certain modernists now belabor orthodox Catholics for being “Pelagians” for simply taking the Gospel seriously, while simultaneously teaching that a “good” atheist can go to heaven by his deeds. That is the true definition of Pelagianism, for the Bible and the Church have always taught that a man can not be saved by his good works, without the blood of Jesus Christ. 1

So, put it all together, and you can see that there is no pendulum swing. Catholicism was Catholicism in every century ubique, semper, et ab omnibus except the 4th century and the 20th century. St. Athanasius taught in that first crisis that the only way back to the source is to see what Christ and the Apostles taught in unbroken Magisterial authority in faith and morals, unbroken in a straight stream (with only slight diversions of style and discipline) for every century before his own.

Mary, the destroyer of all heresies, will lead us back to Her Son Jesus, and the beliefs of her dear and earliest Christians.