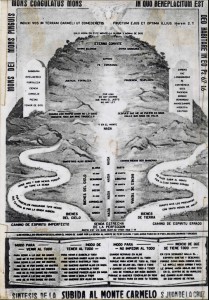

The above picture is a remake of the spiritual life as drawn and described by the greatest ascetical theologian of the past millennium, St. John of the Cross. St. John of the Cross was a 16th century Carmelite whose feast day we celebrate today in the TLM (a couple weeks out in the new calendar.)

If you look at that picture (which is hard to see but phenomenal if you can expand it) you will see that the man or woman who sets out to seek God is called to a narrow path that not only despises any earthly attachments that prevent union with God, but also despises any self-centered heavenly attachments that keep one from God. If one succeeds, one arrives “upon this mountain where dwells only the glory and honor of God.” Not to sound emotional, but I get chills in what it says before that point: “eternal invitation.” In other words, St. John of the Cross believed that God would admit us to the heights of union not only in heaven but also on earth.

But this was only for those who went by the rare path, which (in the above picture) reads nada, nada, nada. As you know, that means nothing, nothing, nothing. That means no candy bars and it means means no spiritual pride for those who want to arrive at the flame of living love upon Mount Carmel. Nothing means nothing except God. God alone. Soli Deo.

To some Catholics in the past 50 years, nada sounded like Buddhism. Why? Two reasons. First, because the third Noble Truth of Buddhism is that suffering can be extinguished by extinguishing desires. At first blanche, they didn’t seem too far off: St. John of the Cross also proposed a way of total extinction of unruly desires. The second similarity is that Nirvana means nothingness. Nirvana is the ultimate goal of the Buddhist who has taken the spiritual life seriously. So if Nirvana means (in a certain sense) nothing, then how is Nirvana really any different from the Catholic saint’s nada, nada, nada?

St. John Paul II did his first thesis on St. John of the Cross, and later as Pope he helped to shed light on potential syncretism by reminding the Catholic that Buddhism carried a “negative soteriology.” “Soteriology” is the study of salvation. By “negative,” St. John Paul II did not mean “grumpy” but that Nirvana as salvation ended in nothingness, where the goal of the threefold nada for St. John of the Cross was…

…God Himself. St. John of the Cross lived the primacy of the spirit over the body (Romans 8) but not within some form of ancient Manichaeism or modern masochism or enlightenment Cartesian Dualism. He lived the nada, nada, nada to arrive at todo, todo, todo…everything. Where Nirvana’s termination point is nothing, the termination point of the Carmelite is everything:

So let no one boast in men. For all things are yours, whether Paul or Apollos or Cephas or the world or life or death or the present or the future—all are yours, and you are Christ’s, and Christ is God’s.—Col 3:21-23

In Buddhism, Nada is both the means and the end. In Catholicism, nada is only the means (and at that, quite a different path because of what it means to be baptized and follow Christ in love, not simply a selfish ascetical struggle.) Nada is simply the means for John of the Cross, not the Nirvana extinction point, for John wanted his readers to arrive “where God is pleased to dwell.” Where is that? Upon Mount Carmel where all selfishness and spiritual pride has been extinguished. There, an even more ancient John “heard a loud voice from the throne saying, Behold, the dwelling place of God is with man.”—Apocalypse 21:3

Yes, Buddhism is extinction. Catholicism is where God is pleased to dwell with man forever.

I have read about 300 of the 400 pages of the collective works of St. John of the Cross, but the best summary I could give came from a simple youth group board I saw at Nativity parish in Colorado: The more you pour out, the more God pours in.