Realizing that most of my readers are lay, and realizing how the priest—child scandals have tanked not only the low trust placed in celibates not only by secularists but even by good Catholics, this blog has to tread on pretty raw ground. Let me stay at the outset that although Divine Revelation definitively holds it as true that celibacy is a higher vocation than marriage, the saints are clear that the priest’s salvation is normally harder to attain than that of a lay person, due to the higher level of scrutiny at his particular judgment. This is obviously due to the duties and high-calling he has ostensibly answered in life.

I will show you quotes from Our Lord and St. Paul, the Council of Trent and one amazing story from the Desert Fathers to demonstrate this. Notice that all those sources (except the last) are dogmatic, not devotional. In other words, the fact that celibacy is a higher calling than marriage is infallible. Trent even attaches an anathema (condemnation) to denying it. But the reason it celibacy is greater than marriage is not some Albigensian rejection of the body or marriage in-se or even intercourse itself.

Rather, celibacy is higher because everyone who makes it to heaven will already be in a state of non-sexual relations, regardless of what they lived on earth (marriage or celibacy.) This is not because we won’t have bodies. In fact, at the general judgment “forwards” (an inaccurate term for eternity, granted) everyone who is saved will both have their physical bodies and be in a state of non-sexual-relations for trillions and trillions of years to follow. (In fact, that last statement will strangely also be true for everyone in hell.)

In other words, celibacy is a higher calling than marriage not because celibates are better people than married people on earth, but because it’s the pre-emptive heavenly state already begun on earth, provided it can actually be lived in generosity. But there is a lot of anecdotal evidence that it is not lived well among Roman Catholic men. Was this always the case? No. The Apostles left their wives and lived celibacy perfectly. (Of course, the young and courageous St. John who was a perfect virgin his whole life, so he had no wife from whom to ask or demand leave.)

Christ’s ideal of for celibate men and women to be living on earth is the pre-emptive heavenly-state. Along these lines, I believe the most overlooked line on this comes from Jesus Christ Himself:

And Jesus said to them, “The sons of this age marry and are given in marriage, but those who are considered worthy to attain to that age and to the resurrection from the dead neither marry nor are given in marriage, for they cannot die anymore, because they are equal to angels and are sons of God, being sons of the resurrection.—St. Luke 20:34-36

St. Paul: Celibate Apostle, Catholic Bishop, Martyr.

St. Paul also encourages everyone reading his letter to the Corinthians to be celibate, as he is:

I wish that all were as I myself am. But each has his own gift from God, one of one kind and one of another. To the unmarried and the widows I say that it is good for them to remain single, as I am.—1 Cor 7:8.

Of course, people will say to the above quote, “But if St. Paul just said ‘everyone has their gift,’ then why should the default for the serious Christian be celibacy instead of marriage?” This is a good question. But the full-answer comes in the very next verse:

But if they cannot exercise self-control, they should marry. For it is better to marry than to burn with passion.—1 Cor 7:9

It’s not very romantic, but St. Paul is here saying marriage is a concessionary prize. Sadly, the modernist view is the opposite: “The homosexuals and incels become priests just to make their lives look legitimate.” At the empirical level, I hate to admit there’s a small amount of truth to this. But in happier days in the Church, the strongest and most courageous (not the child-molesters) became celibates.

St. Thomas More, the English married-lawyer and martyr for the Catholic faith in the 16th century, once said he had decided to be “a chaste husband rather than a licentious priest.” Of course, he was not conflating chastity with celibacy in that sentence. He meant it’s better to be a married man who unites naturally with his wife in the marriage bed (that is, chaste according to the married state in life) than be a so-called-celibate priest who does not actually live up to his promises to celibacy (hence, licentious.)

St. Thomas More, saint, martyr, husband, father, lawyer.

But sometimes the notion of seeing marriage as a “concessionary prize” doesn’t only have to do with “the burning in the loins” but may have to do with it as a positive gift. Think about how the parents of St. Therese of Lisieux had first tried religious life, but ended up (of course—before final vows or ordination) leaving celibacy to marry each other. But this still proves the point of St. Paul: The default was to first cling to the Lord with an undivided heart. This is usually the most generous approach to the gift of our lives to God, and then God (or the burning in the loins) can let us one be destined for the concessionary vocation. (Yes, I know this is extremely politically incorrect after Vatican II.)

Let’s switch gears to 2023. As most of you know, there are very few religious orders and no dioceses in the world to which I would encourage young people to apply. Also, high levels of addiction to porn even among serious young Catholics in the 21st century mean that most straight people who would normally be celibacy-minded may not be able to “cut it” in celibacy. I wish it were different, but the high-levels of porn addiction even among young daily Mass Catholics shows their loins will burn without marriage. But this too is misleading. Why? Because marriage never solves porn addictions. Thus, the only solution is that young people must end their pornography before discerning any vocation in the Catholic Church.

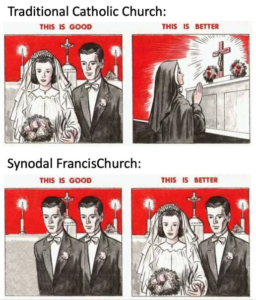

Also, there is the additional spiritual and emotional weight of attempting to join traditional religious orders when the Vatican is attempting to shut down all faithful communities, even before Traditiones Custodes. The Vatican is promoting same-sex civil-unions and persecuting traditional religious communities. Thus, this meme is not an exaggeration at all:

The high level of canceled-priests and the crisis in the Church shutting down good, traditional religious congregations for women is one reason I have encouraged people to discern being a single-celibate or consecrated-virgin for the kingdom in this talk I gave in Louisiana several years ago. Yes, I obviously think it’s dangerous for a celibate to live alone. But if one has the gift of celibacy and can’t find a solid community, then single-consecrated life is at least something to pray about.

Back to the main point of this blog: It’s to only show that it’s dogmatic, not devotional, that the Bible and the Catholic Church hold celibacy to be objectively higher than marriage, even if celibates often subjectively fail at it. The Council of Trent is considered infallible when it makes anathema (“be condemned for rejecting this…”) statements. One such statement reads thus:

CANON X.—If any one saith, that the marriage state is to be placed above the state of virginity, or of celibacy, and that it is not better and more blessed to remain in virginity, or in celibacy, than to be united in matrimony; let him be anathema.—Council of Trent chapter 24, Canon 10.

Thus, it is more blessed to be celibate than married, as the above Council of Trent says, as well as Our Lord in Luke 20 and St. Paul in 1 Cor 7. However, it is also more dangerous, as we will soon see.

The fact that celibacy entails more glory in heaven (if one actually succeeds in getting there in such a dangerous state as celibacy) reveals why celibacy also entails much more spiritual attack here on earth. Therefore, the following account from the Desert Fathers should be both an encouragement to all young readers to try first celibacy for the Kingdom of God while remaining a cautionary tale what opposition you will face in this life if you try to give your whole life to God:

One of the hermits in the Thebaid used to say that he was the son of a pagan priest, and as a little boy he had often seen his father go into the temple and sacrifice to the idol. Once, when he had crept in secretly, he had seen Satan on his throne, with his host standing round him, and one of his chief captains came and bowed before him. The devil said, ‘Where have you come from?’ He answered, ‘I was in such and such a province, and there I stirred up wars and riots, and much blood was spilt, and I have come to tell you.’ The devil asked him, ‘How long did it take you?’ He answered, ‘A month.’ Then the devil said, ‘Why on earth did you take so long over it?’ and ordered him to be beaten. Then a second came to bow before him and the devil said to him, ‘Where have you been?’ The demon replied, ‘I was in the sea, and I raised storms, and sank ships, and drowned many, and have come to tell you.’ The devil said, ‘How long did that take you?’ He answered, ‘Twenty days.’ The devil said, ‘Why ever did you take so long over this one task?’ and ordered him also to be flogged. Then a third came and bowed to him and the devil said to him, ‘What have you been up to?’ He answered, ‘I was in such and such a city: and during a wedding I stirred up quarrelling until the parties came to bloody blows, and in the end even the husband was killed, and I have come to let you know.’ The devil said, ‘How long did it take you?’ He answered, ‘Ten days.’ The devil commanded him also to be flogged because he had been idle. Another came to adore him, and he said: ‘Where have you been?’ He answered, ‘I was in the desert: and for forty years I have been attacking one monk. At last in the night I prevailed, and made him lust.’ When the devil heard this, he got up and kissed him. Taking off his own crown, he put it on his head, and made him sit with him on a throne, and said, ‘You have been brave, and done a great deed.’ When I heard and saw this, I said to myself, ‘Great indeed is the discipline of the monks.’ So it pleased God to grant me salvation: and I went out, and became a monk.—Desert Fathers, Sayings of the Early Christian Monks, Chapter 5, On Lust #39, edited by Benedicta Ward.